This is a mish-mash of follow-ups to previous newsletter editions, including some great feedback from some of you which I always appreciate.

(1) The overlap between FTX and funny business in cattle feeding (link)

NPR did a podcast series on the $244 million Tyson Foods / Easterday saga of 265,000 ‘ghost’ cattle that existed only on paper. Ooph, it was a doozy and well worth the listen.

My big takeaways from the way NPR told the story were that ‘trust but verify’ isn’t just a nifty saying, but also the reminder that in most situations like this, the person doesn’t set out to blow up their business/life, it happens over time as need and opportunity collide.

At the risk of stating the obvious, both the FTX saga and the Tyson/Easterday saga point to the rationale for better governance & systems that reduce the opportunity for bad behavior in the first place.

(2) 1975 should call the pork people (link)

The feedback on this one was fun because it generally fell into 3 camps:

- Multiple producers reached out to highlight that there are already pockets of high-quality pork production in the US, like Berkshire programs or brands out of Clemens Foods Group, for example. And yet, they also readily admit there’s still an industry-level quality gap that the pork industry has not solved while the beef industry now has a super high percentage of carcasses that grade very high quality.

- There have been prior attempts in the US to implement quality grading, including recent attempts. But the pushback from packers is that the increased complexity of plant logistics are not worth the benefit. While it makes sense that anything that hampers throughput is met with skepticism, this pushback strikes me as over-weighting the short-term costs against the long-term rewards of being able to grow the fresh pork pie, so to speak. Fresh pork has as big of an adoption problem as farm management software, and it seems like it’s going to take a new approach to the business model or branding or something (and probably something big) to solve it.

- Fresh pork as a meh kinda product is a US issue, not European for example, as evidenced by products like Iberico pork which “comes from the distinctive Black Iberian Pig. Native to areas of Portugal and central and southern Spain, the pigs’ diet of acorns and elements of the natural forests in these areas impacts the meat directly, giving it a nutty, evocative flavour. Black Iberian Pigs – also known as ‘Pata Negra’ – are bred to contain a higher fat content than many other pigs. That means that the pork they produce has a delightful tenderness that is sure to impress foodies.” While this is a great example, it’s clearly a specialty item and not the everyday version of pork that middle-class meat eaters are putting on the table.

(3) Lunatic farmers (link)

I love finding comments in the wild that support an idea. When we talk about lunatic farmers doing things that look absurd to the coffee shop boys until suddenly they look brilliant, here’s a great example of that dynamic in action:

(4) It’s time to call it: farm mgmt software was a wash. (link)

Shane Thomas and Rhishi Pethe built on my analysis with their own comments that furthered the conversation.

In Upstream Ag Insights Shane framed his analysis around network effects (or lack there of):

The first thing to consider is what underpins a “winner-take-all” market? The answer: Network effects.

Network effects are the incremental benefit gained by an existing user for each new user that joins the network. Every additional user to the telephone creates a stronger network effect. Same with Facebook or any social media.

The assumption in the farm management software space was that as more acres were gained on a platform, that would mean more data accrued leading to a deeper understanding of that customer and therefore deeper value delivery to the farmer which would mean more data for the organization to add value to other farmers which would increase switching costs of the farmer and make it difficult for any other farm management software player to break into the market. Farmers in theory would derive so much decision making value they would gladly play $5, $7 or $10/ac to access this. A winner-take-all scenario.

Because of these assumptions the emphasis became customer acquisition. Hundreds of million (billions in total) poured into pulling customers onto the software.

What’s important to note is that in order for a network effect to take off there needs to be utility for the user and ideally a tight feedback loop. Think of Google. Everytime you search on their platform you derive utility, almost immediately. And Google has a tight feedback loop surrounding time spent on the page, what you clicked on etc. ultimately enhancing their offering and making them better which means you keep going back to Google. The externalities influencing the system are close to none and there are only so many parameters that can influence the outcome.

Now if we think about this from a farming perspective, we get the opposite. The first issue is that the farmer has an arduous onboarding process and not only doesn’t derive immediate benefit, they might not derive any benefit for months, or years. This stems from data challenges and disparate connectivity issues.

Rhishi Pethe, who writes Software is Feeding the World, put it this way:

Janette is spot on in her analysis of a flawed market being a winner-take-all market. The faulty winner-take-all assumption was compounded by a few other factors. When Monsanto acquired The Climate Corporation, the assumptions on productivity improvement through analytics were in the range of 15-20 bushels per acre, when the prices of corn and soy were some of the highest prices in the history of commodity markets.

Even as late as 2017, it was common to talk about improvements in profitability of $ 100 per acre, based on farm management software analytics. It created an overhang on farm management software companies like The Climate Corporation (full disclosure – I worked there from 2017 to 2020), and Granular. There was a belief about creating a data flywheel to continue to drive more value and in turn bring in more data from commodity row crop farmers and drive even more value. The reality was a bit different.

I want to highlight my conclusion once again because some folks seemed to skip that part😉

So, what do we learn from agtech 1.0?

About pricing new products, and how people don’t tend to value what they don’t pay for.

About user experience and automating data entry.

About value creation….and that there has to be enough of it!

About how digital products matter strategically for incumbents, and that checking a box is not a strategy.

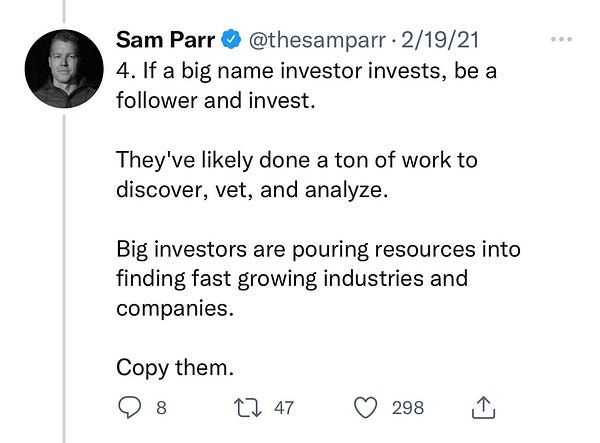

I also think there are lessons about aligning financing and business expectations with long-term customer interests. Agtech 1.0 created the opportunity, or revealed the opportunity, for sector-focused investors to have an edge over generalist VC’s simply by understanding the business of agriculture and its nuances.

While it’s time to call Agtech 1.0 a wash, I don’t think we can call it a bust.

It attracted capital and talent to a previously overlooked space. And even though you can’t point to individual significant long-term successes in this category, we can safely assume the learnings that founders, investors, strategics, and farmers had through this process has informed how Agtech 2.0, 3.0, 4.0…25.0 will play out.

Oh and the whole thing of not knowing exactly how things will play out, isn’t that really a feature of creating and building the new, not a bug?

What a time to be alive 😉