Ugh. That was my reaction when my book club chose a book about life in a Mumbai slum called, ironically, behind the beautiful forevers.

We normally read historical non-fiction narratives like The Splendid and The Vile, Endurance, and The Warburgs. Books that have that great combo of inspiration and interesting information. Not books that make me want to cringe at the bitter reality of people sharing the planet at the exact same time I am and yet our lives could not possibly be more opposite.

I just finished this book and am left with a simultaneous sense of relief (thank goodness the book is over and I can go back to my bubble) and lingering dread at the weight of a book like this that kinda seeps into your soul and gets stuck. It’s the reminder of real human suffering because someone put a name and the specifics of a story to a statistic, to the million ways that poverty slices at human dignity, as the struggle to meet the most basic needs of survival leads to the horrors of corruption, parents forced to choose between awful and terrible options to keep their kids fed, etc.

Ugh, indeed.

And yet, contrary to popular assumption there’s so much reason to celebrate progress and to be optimistic; there are fewer people in extreme poverty today than ever before, both in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the total population.

This outdated mental model from ‘our world in data’ stands out:

“Two centuries ago the majority of the world population was extremely poor. Back then it was widely believed that widespread poverty was inevitable. But this turned out to be wrong. Economic growth is possible and poverty can decline.”

Clearly, the reasons behind the positive story in this chart are multi-factorial, but industrialization and continued innovation have played a major role in reducing the number of people on the planet in poverty, including agricultural innovations. (After all economic development in developing economies is, by definition, agricultural development.)

That inflection in 1950 is interesting, while I don’t what caused it, I wonder…

…what if the real promise of agtech is to be the next inflection point to elevate more people from extreme poverty?

This whole topic converges with Prime Future’ish topics when you set it next to:

- The seemingly unending discussion <waves hands> about reducing the GHG footprint of livestock.

- The discussion about whether animal agtech is venture viable.

If we want to reduce the global GHG footprint of livestock, meat & dairy, then emerging markets have to be the focal point for interventions and innovations.

A lot of capital is being plowed into reducing methane emissions in livestock but largely for regions with livestock production systems that are already highly efficient, especially in comparison to their counterparts in developing economies. Not only are many of those solutions only nominally interesting in terms of value creation for producers (and tbd for consumers), many are also only nominally interesting in terms of the job those interventions would be hired to do which is to reduce the global GHG footprint of livestock.

I recently heard Frank Mitloehner from UC Davis say that ~80% of the global livestock GHG footprint comes from developing economies.

So focusing on reducing the GHG footprint of the beef industry in the US or the dairy industry in New Zealand is just playing around the edges of the global problem, at best. Mathematically, it just doesn’t matter much.

If reducing the global GHG footprint is the goal, then the biggest impact is far and away to be made by enabling emerging economies to shift from smallholder agriculture to commercial-scale agriculture to become, by definition, more efficient in the business of producing meat, milk and eggs, and simultaneously lower the GHG intensity.

As an example, as more innovations unlock value in India’s dairy industry, will they still have 200 million dairy producers milking 300 million dairy cows & water buffalo in 20 years? In 10 years? Maybe it becomes 100M producers milking 80M cows as they increase output with less animals – that’s the history of the US beef and dairy industries, as well as other highly efficient markets. Better economically & environmentally.

(The CLEAR Institute did a great write-up on this phenomenon and why efficiency has to be part of the GHG conversation.)

All of this unlocks the basic economic idea of specialization – those who are good at the business of producing milk produce more milk and those who are not good at it go find something else they are good at that contributes to the economy.

But obviously, the challenges that developing economies face are incredibly complex; if these were simple problems they’d be solved by now. I don’t mean to sound reductive, and in no way am I suggesting that agtech is, will be, or ever could be The Answer for developing economies…but ag innovation can be a piece of the puzzle.

And we know this is possible because we’ve seen it happen before.

Exhibit A: Norman Borlaug’s work on dwarf wheat. (If you haven’t read his biography, you’re missing out – incredible story of the ridiculously high impact potential of ag innovation.)

The question is which agtech solutions can be as high impact as dwarf wheat?

Changing agricultural economies requires things we take for granted in places like Ireland, Canada, or France….things like access to capital, access to efficient markets, access to buyers with high-value processing capacity, strong risk management tools, etc. Those sound like problems agtech can at least play a part in solving, don’t they?

(Tho of course, you need things like natural resources, roads, access to water, electrification, political peace, reliable governments, strong property laws, etc – none of which agtech can solve.)

Oh, and VC’s want venture returns to justify continued agtech investment? And agtech founders want to create real value for the world?

It’s not gonna happen with marketplaces in the US. Replacing relatively efficient analog marketplaces with digital marketplaces does not create much value here, it’s incremental at best.

But mention marketplaces to Mark Kahn from VC firm Omnivore that invests in agtech companies in India and he’ll tell you marketplaces can change entire sectors by giving buyers and sellers a cost-effective means to connect and transact.

In emerging markets that are mega fragmented and low yielding, agtech innovations can be legit game-changing. And not just marketplaces, all the things we throw in the agtech bucket.

What if the real promise of agtech is that the combination of existing & emerging tech with existing & emerging business models can actually change economic trajectory?

We can keep funding agtech that tweaks around the edges of production in developed economies, or we can direct technology and solutions to the places where they can create the largest delta, the most change between current state and future state.

Clearly this isn’t a new idea tho, I’m late to the party – there’s a lot of startups and investors who are way ahead in this idea of far greater potential for emerging agtech in emerging markets.

Maybe I’m having an agtech crisis of belief, or maybe I’m just tired of talking about first-world problems like how to make the really efficient thing marginally more efficient.

Either way, maybe emerging markets really are the path forward for agtech to make its dent in the universe.

Not for the sake of cool tech but for the sake of progress that actually enables human flourishing. At the end of the day, isn’t that what it’s all about?

I think Norman would have said so.

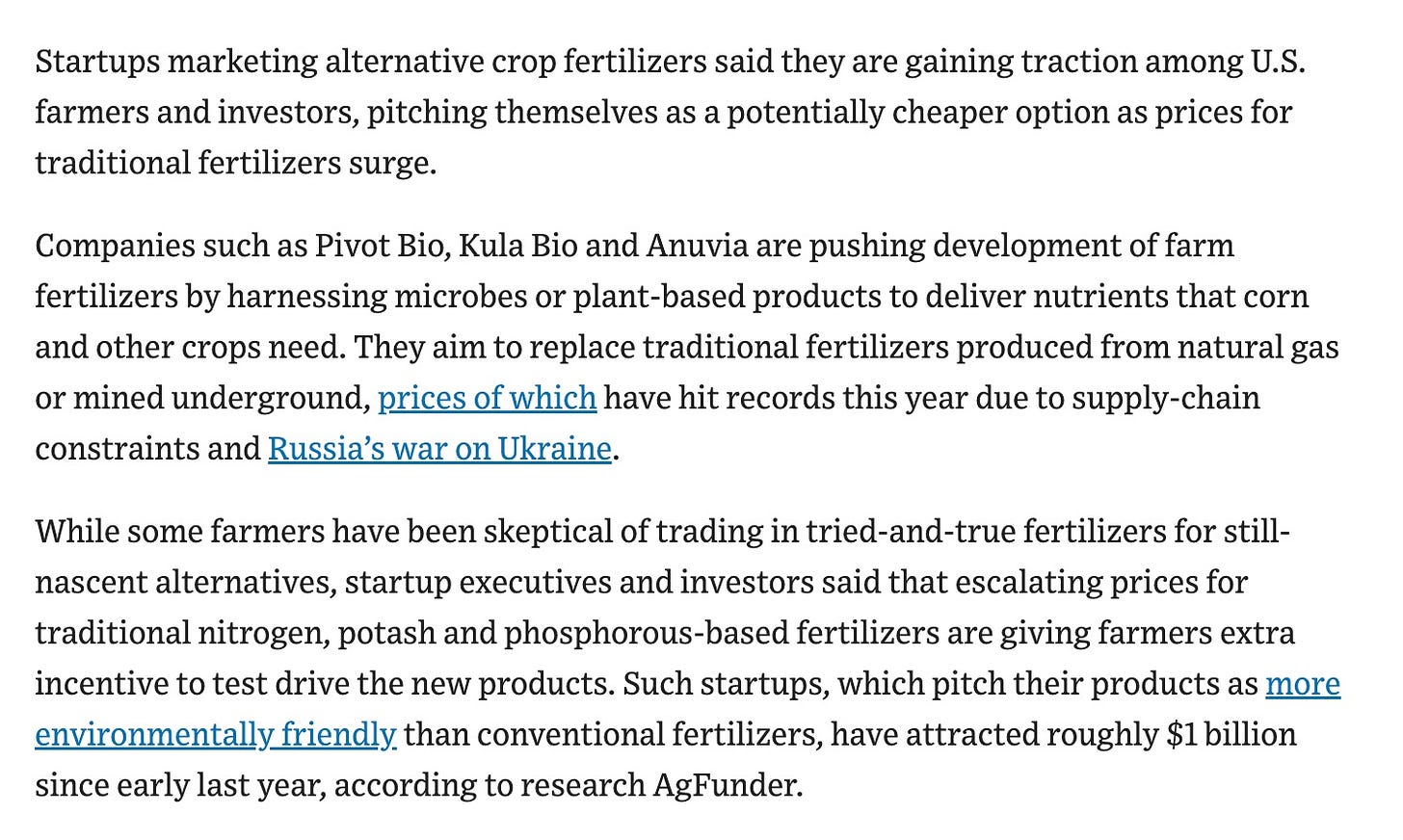

That is the headline from a recent Wall Street Journal

That is the headline from a recent Wall Street Journal