This week we throwback to Prime Future 68 as a welcome to new followers & as the setup for next week.

There’s a local ranching family that’s been raising cattle on the same land for 7 generations. In that time they have not sold an acre of land, not one. They have withstood droughts, drug cartel activity, wildlife predators, market crashes, high interest rates. You name it, they’ve survived it.

Some years ago they got into a lil spat with the US government over the renewal terms for grazing permits on public land, so the federal government rounded up the family’s cattle that were on public lands and kindly delivered them to the sale barn.

Someone recently summarized the family’s mentality this way, “They are fiercely independent, they just don’t trust anyone. Then again, that’s probably how they’ve survived and why they’re still ranching.”

This struck me. I have a deep respect for the challenges producers face and the resilience they embody….but I wonder if that fierce independence won’t actually work against producers in a rapidly evolving world where collaboration is rewarded more than independence. (And though this first example is a rancher, every segment of the value chain has players with a similar mentality, a transactional ‘us vs everyone else’ mentality.)

Collaborating raises new questions, new situations, new risks to manage…and new opportunities. If done thoughtfully and effectively, new collaborators can grow the pie (and it’s individual slices) in ways that independent actors cannot.

In today’s world, mastering the art of highly effective collaboration increases the probability of survival.

Let’s start with one of the most successful examples of a systems approach, one that has stood the test of time: McDonald’s. (If you aren’t familiar with the 3 legged stool model, here’s a good primer.)

Each supply category has a limited number of suppliers that are held to very high standards but rewarded with high volumes of business, typically on a cost plus basis. Suppliers do not float in and out of the system frequently, these are not transactional relationships – they are partnerships built for the long term.

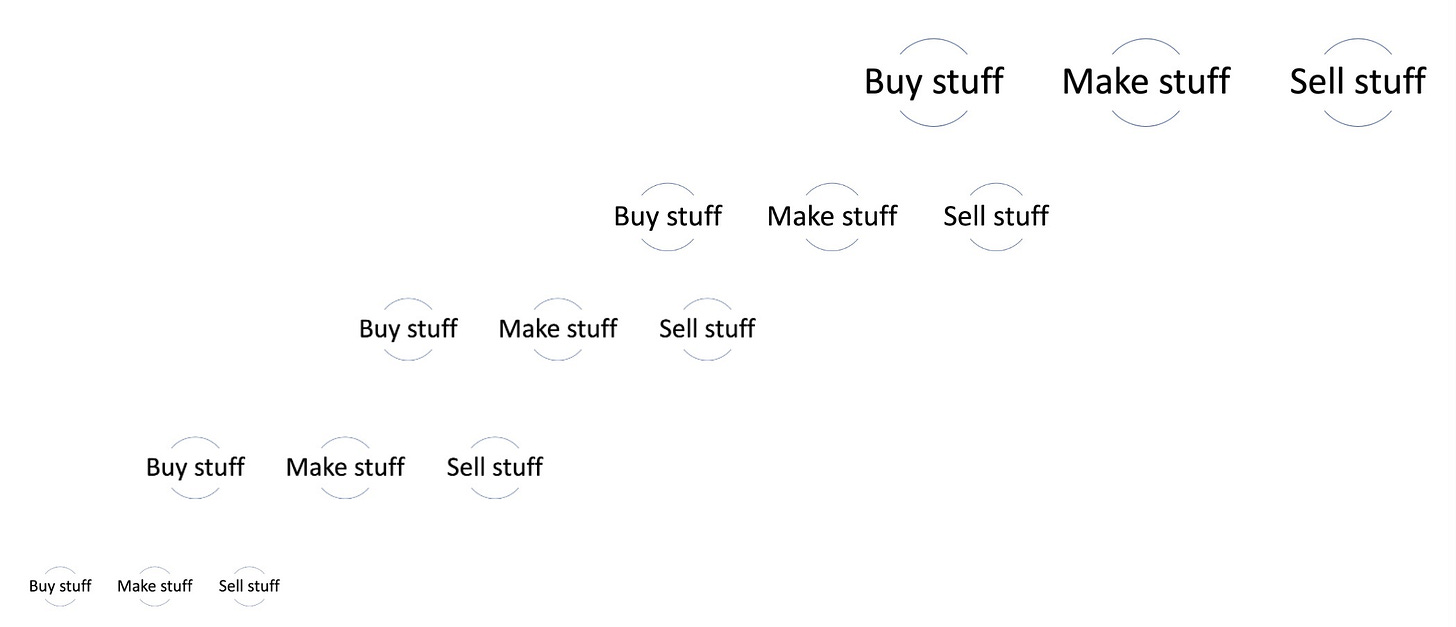

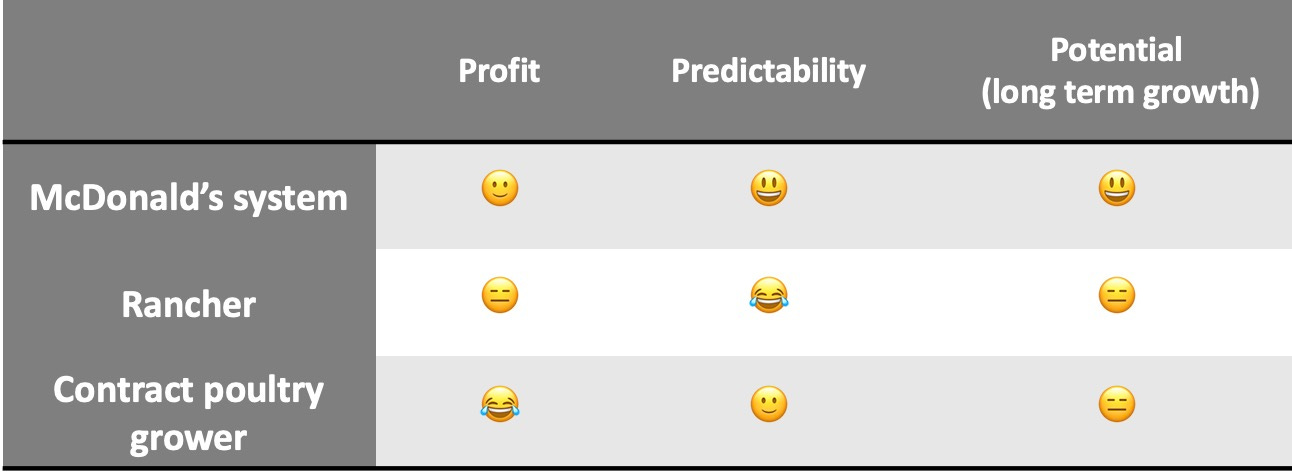

Now contrast the McDonald’s system with two alternative structures that land in different places along the continuum of Transactional to Collaborative, the independent rancher and the contract poultry grower:

- Let’s assume the rancher sells weaned calves at the sale barn, the epitome of price taking at the market’s daily whims. The definition of transactional – the buyer is literally whoever is willing to pay the most on any given day.

- Let’s assume the contract poultry grower supplies the labor and facilities, then executes the management program prescribed by the poultry integrator. The grower is paid on a $.xx/lb produced with some level of base pay that is set, and the remainder of pay determined by how the contract grower’s live performance stacks up against the flocks that are processed that week (the lottery system).

Regardless of the business (weaned pigs, broilers, or hamburger patties), it seems there are 3 core drivers around engaging in collaborative ecosystems with dedicated partners:

Profit.Maybe its about finding higher value races to the top of the value pyramid, rather than vice versa. Maybe it’s about cost plus arrangements that may not maximize revenue on a given transaction, but could look smart over the long haul and the ups & downs of market cycles.Predictability.Creating predictable revenue can radically impact business planning and operations. Some would prefer to make $.1/lb day in day out, some would prefer to make $1.00/lb on 1 load knowing they might lose $.90/lb on the next.Potential (long term growth).What’s the growth potential of the ecosystem? Is this a chance to grow the pie and grow your business accordingly?

Below is a rough analysis of how different systems compare – maybe these are over or under stated, but the big idea is that there are tradeoffs under each model.

Of course this doesn’t capture some of the intangible tradeoffs of collaborative partnerships, like losing some degrees of freedom. I think my real point is that there are increasingly more alternative ways to approach business models and these alternatives should be considered.

- What is the upside potential? Downside risk?

- What are the tradeoffs compared with the risks of the status quo?

- Are those tradeoffs bearable compared to the next best alternative?

The answer to those questions will always be situation/people/goal dependent.

And I’m no Pollyana – there are risks with entering partnerships where multiple parties are reliant on one another. The obvious caveat is that not all systems are created equal; not all partners are good partners, not all collaborations are worthy bets. Sometimes the business model isn’t right, sometimes the leadership isn’t right…or any other number of reasons that a system doesn’t work out.

One of the most practical pieces of advice came from my friend’s dad: when you create a plan to enter a partnership, create the plan for how you will exit the partnership.

(Those of you much more seasoned than me are probably nodding your head vigorously at that advice since you’ve seen the dangers of not preparing for partnership dissolution in advance. “Hope for the best, prepare for the worst” and whatnot.)

A great irony from a producer standpoint is that although it might be easy to reject taking on the risk of entering partnerships, the fewer strategic alliances a producer makes with customers, by definition, the more reliant the producer is on commodity markets where price takers have zero control which introduces…risk.

Maybe the real questions are around where you want control (price? management freedom?), where you want predictability, and what type of risk you are willing to accept or are more comfortable managing.

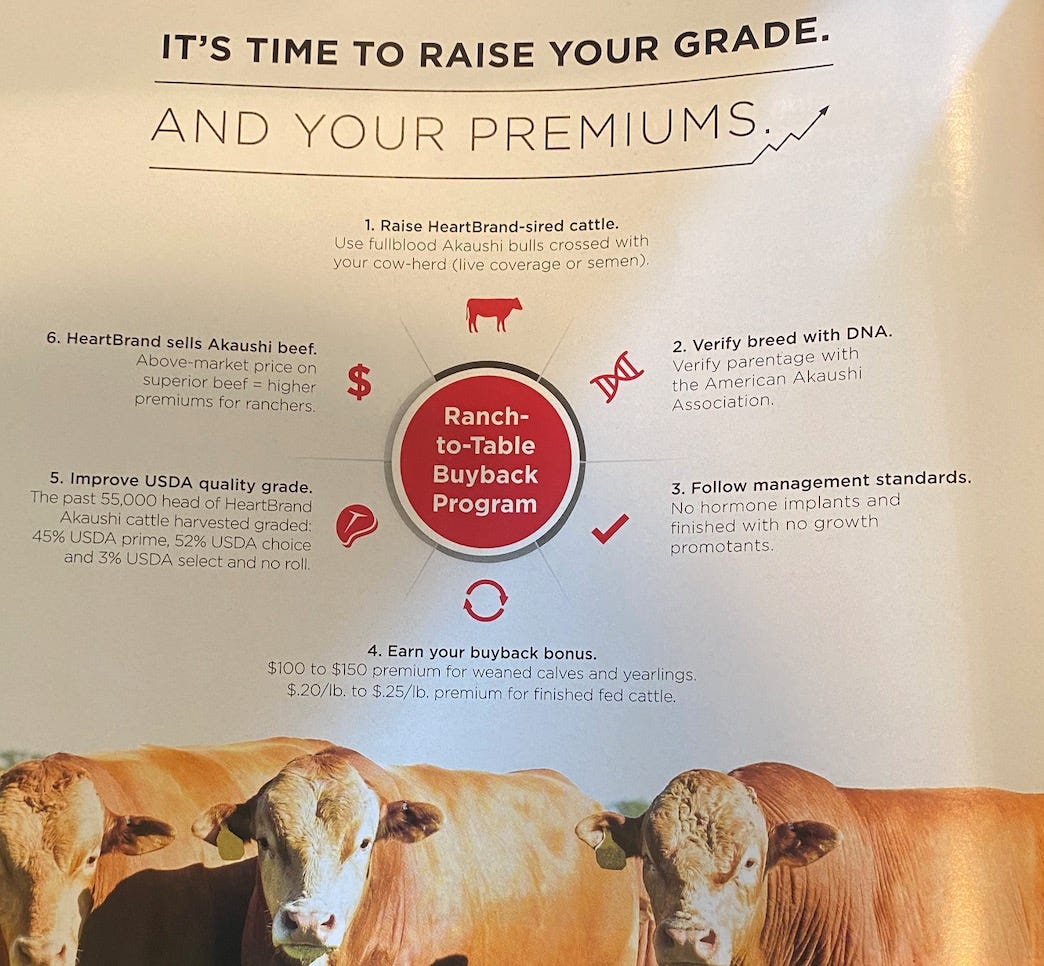

I recently saw a list of about 30 aligned beef supply chains in the United States, here’s a snapshot of one. ‘Run our program to help us deliver a better product to our customers and we’ll all win’ is the summary idea. If you read Prime Future you know I think we’ll continue seeing more of these:

The above examples focus on how producers might engage supply chains & customers, but what about managing suppliers? I recently heard of a producer who decided to double down on supplier relationships by choosing one strategic supplier for every major input category. They gave up the transactional, shop-around-for-the-best-price-on-this-transaction in pursuit of the best supply arrangement on the next 1,000 transactions. Another dimension of a collaborative approach.

What does collaboration look like in Agtech?

Now let’s talk about where a collaborative mindset can drive progress in agtech:

Among co-founders– its doable to be a solo founder but as someone who hit The Great Wall of Burnout trying this route, I can tell you it is HARD and there is not an ounce of virtue in trying to defy the odds by being a solo founder.Among founders and venture investors– there are huge tradeoffs in choosing to bootstrap a business which typically means slow and steady growth versus raising venture capital and committing to the high growth model. Neither is right or wrong, they are just different models with different paths.Among founders and early customers– That early feedback from first customers – and how founders respond – can set the entire trajectory of an early stage company. Ask any successful tech company and they will tell you about the early customers who made them.Among big companies and startups– each brings something to the table in terms of successfully scaling innovation, figuring out how to get the best of each can unlock magic.Among startups and startups– the punishment for tech forward producers right now is that every single hardware/software product tends to have its own login. What farmer wants to login to multiple systems to manage their business? Zero. But not every company can be THE platform. This will drive partnerships that may not be what every company wants, but will drive customer experience and <drumroll please> grow the pie of tech adoption.

The best summary of those last points came from a recent Future of Ag podcast interview with Jim Ethington, an early employee of Climate Corp who is now CEO of Arable:

“We could have said we can’t afford to give up a piece of this pie and we’re going to go it alone but that’s not the path that moves the industry forward. …we can all be good at our pieces and hey sometimes we compete, most of the time we can collaborate but that’s what moves the industry forward.…being able to put the puzzle pieces together where 1+1 = 3 for the customer.

What if they try to replace us? Come in with the assumption that a) it doesn’t matter because this integration is what the customer wants – start with the customer and work backwards, and they want one integrated system. …and b) when this plays out even at the largest companies in the world…guess what their roadmap is full. ….everybody’s roadmap is packed – don’t flatter yourself they aren’t going to go build your product. And if they do, they were probably going to anyway and your partnership didn’t do anything to accelerate it. I think you have to let go a little bit and go back to the customer problem, growing the pie, making this a better overall technology space….and put aside the natural fears of what risks does this pose to us. The benefits outweigh the risks because those fears usually aren’t as real as you think.”

Does an independence-at-all-cost mentality create the trajectory to thrive in the ag economy of the future?

There’s perseverance in independence that will get you somewhere.

But my hypothesis is that moving forward it will be the smart collaborators who channel that same perseverance for the sake of a larger business objective who will win; those who grow the pie in a way that creates long term value for every link in their chain.

…aka the spoils will go to the effective collaborators. The collaborative’ists, if you will.

“If you want to go fast go alone; if you want to go far go together.”

What a time to be alive 😉

Did you miss early editions of Prime Future?

Access an ebook with editions 1 through 81 here: Prime Future PDF