In the last edition of Prime Future, we kicked off a deep dive into traceability & transparency, and all the complexity (& baggage) those terms carry. Here were my starting hypotheses:

Today we start by looking for more precise definitions. Which matter because it leads into a chicken or egg discussion of which one comes first. Which matters because the drivers are different for traceability and transparency. And drivers matter because they may help us think about how this could play out in the next 10-20 years.

It turns out that defining these two concepts is actually a difficult exercise. Partially because definitions seem to vary by industry and are context specific. Partially because the practical definitions don’t necessarily mirror the textbook definitions.

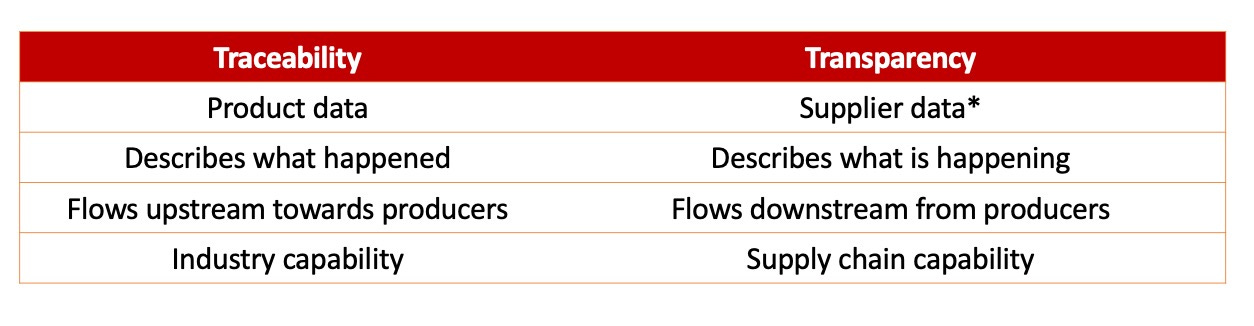

Consider this list of cross-industry supply chain leaders’ opinions comparing the ideas of traceability and transparency:

- “Traceability is the ability to track an item and its associated activities as it progresses through the supply chain. Transparency is the ability to demonstrate this information to stakeholders, regulators, trading parties, and consumers.”

- “Traceability is tracking what happened. Transparency is seeing it while it’s happening. Whereas transparency focuses on mapping the whole supply chain, traceability looks at individual batches of purchase orders as they progress through the supply chain. The data used in traceability allows more targeted recalls, reducing scale and cost.”

- “Transparency is the full view of the supply chain network. Traceability is the view of the supply chain details, including data from sourcing to delivery, which essentially maps the journey of raw materials to finished goods.”

Yet to (much of) the (US) livestock (beef) industry, the contrast in practice is something like:

- Traceability as a stick, transparency as a carrot.

- Traceability as a likely cost, transparency as a potential premium.

- Traceability as mandated, transparency as voluntary.

- Traceability as an animal disease thing, transparency as an anything thing.

We’ll get more into the specifics by protein another day.

Today I want to focus on what these capabilities a-c-t-u-a-l-l-y mean, and I think it’s something like this:

Traceability is the industry capability; transparency is the supply chain capability.

An important point here is that traceability and transparency are capabilities that enable potential value capture, they are not forms of value in and of themselves. Nobody’s putting “this product is from a transparent supply chain” on a retail package and expecting consumers to care.

What they are doing is making a brand promise on a retail package, backed by some degree of information, that matters to an end consumer, such as grass-fed or grain-finished, cage-free or free-range, etc.

Which comes first, the chicken or the egg?

A twist in the definitions is that supplier data, required for transparency, could include product data, which could provide traceability. If a brand has the data infrastructure set up, suppliers are capable of supplying product-level data necessary for traceability, and the incentives are aligned, then a brand with supply chain transparency could also achieve product traceability.

Which raises the question, which comes first, traceability or transparency?

If 4 things could be true here…

- Transparency enables traceability.

- Traceability enables transparency.

- Traceability and transparency are independent capabilities and do not build on one another.

- Traceability and transparency are independent capabilities that indirectly support one another.

….which one is it?

Yes.

I wanted to reach a clear conclusion about whether traceability or transparency has to come first, and which one has more compelling drivers behind it. But my conclusions are that 1) either can be a starting point, and 2) in the end they likely converge and operate in parallel, at least by those who aggressively pursue competitive advantage.

These capabilities can be combined in varying ways across different proteins, different geographies, different degrees of government-mandated traceability, and in different markets with varying degrees of consumer willingness to pay for transparent supply chain claims about specific attributes.

And these capabilities can be applied to varying degrees of granularity and specificity, something that is likely to become an increasing point of differentiation as this trend continues.

Presumably, in some markets/proteins/geographies, industry-level traceability is or will be the foundation that transparent supply chains are built. In others, it is or will be the exact opposite.

This also seems to be a place where the role of export markets in an industry’s sales channel portfolio plays a starring role. Where export markets are a massive driver (e.g. Australia & New Zealand beef), mandatory industry-wide traceability is old hat. Traceability is the leading capability in these markets.

Whether it’s driven by government mandate or industry coalitions, nationwide traceability schemes seem to be the result of high-value export markets.

But I’m not touching the politics of traceability with a 10-foot pole, so I’ll leave it at that observation and move on.

In less export-focused markets, transparency plays the leading role. If transparency is a purely commercial activity, there are a few flavors of commercial benefits:

- Get more money per pound (premiums)

- Avoid getting less money per pound (discounts)

- Maintain or build market access (getting new customers, keeping existing customers, growing business with existing customers)

And these 3 drivers are ultimately driven by brand managers.

Take Horizon Organic milk, who announced last year that they would be carbon positive by 2025 by working with their 600 farmer suppliers.

Idk whether the brand manager doesn’t know that ‘carbon positive’ is the exact opposite of what climate-conscious consumers are interested in or if this was a strategic move to generate buzz around the brand because of the confusion but regardless…

A supply chain-specific carbon footprint is exactly the type of marketing outcome that a supply chain transparency capability enables.

There’s a third concept that could also be a driver of transparency initiatives, and its the concept of supply chain visibility. One explanation I read described transparency as an external-facing capability with commercial benefits, while supply chain visibility is the use of the same information for internal operational benefits.

Imagine doing the one thing (building the transparency capability) and unlocking value via topline revenue (either increased market share or increased price) and simultaneously decreasing costs. That’s a one-two punch to drive the bottom line…

…IF the marketing strategy is aligned with the supply chain strategy.

…IF supply chain participants are incentivized appropriately, meaning those commercial and operational benefits are shared fairly among supply chain partners. Whatever fairly means.

All that to say:

(1) Supply chain transparency, and/or voluntary product traceability, will have the highest adoption where it leads to commercial impact and operational impact for a supply network.

(2) The biggest barrier to supply chain alignment that achieves that commercial impact & operational impact is trust among the supply network, not technology.

(3) Value is in the eye of the brand manager. The tradeoffs around pursuing supply chain transparency, supply chain visibility, and supply chain-specific product traceability will be made at the brand level.

For beef and pork, this means there’s still a whole discussion to be had about whether transparency will get anywhere near the ‘mountain of meat’ of commodity production where there is no brand. Another question for another day.

What a time to be alive😉