Just for giggles, let’s play a game.

Imagine a world in which packers borrowed the retained ownership model and applied it to the meat case.

- How would the risk & reward equation change for packers? for retailers?

- How would incentives change?

- What positive or negative impacts would be felt upstream, if any?

The background:

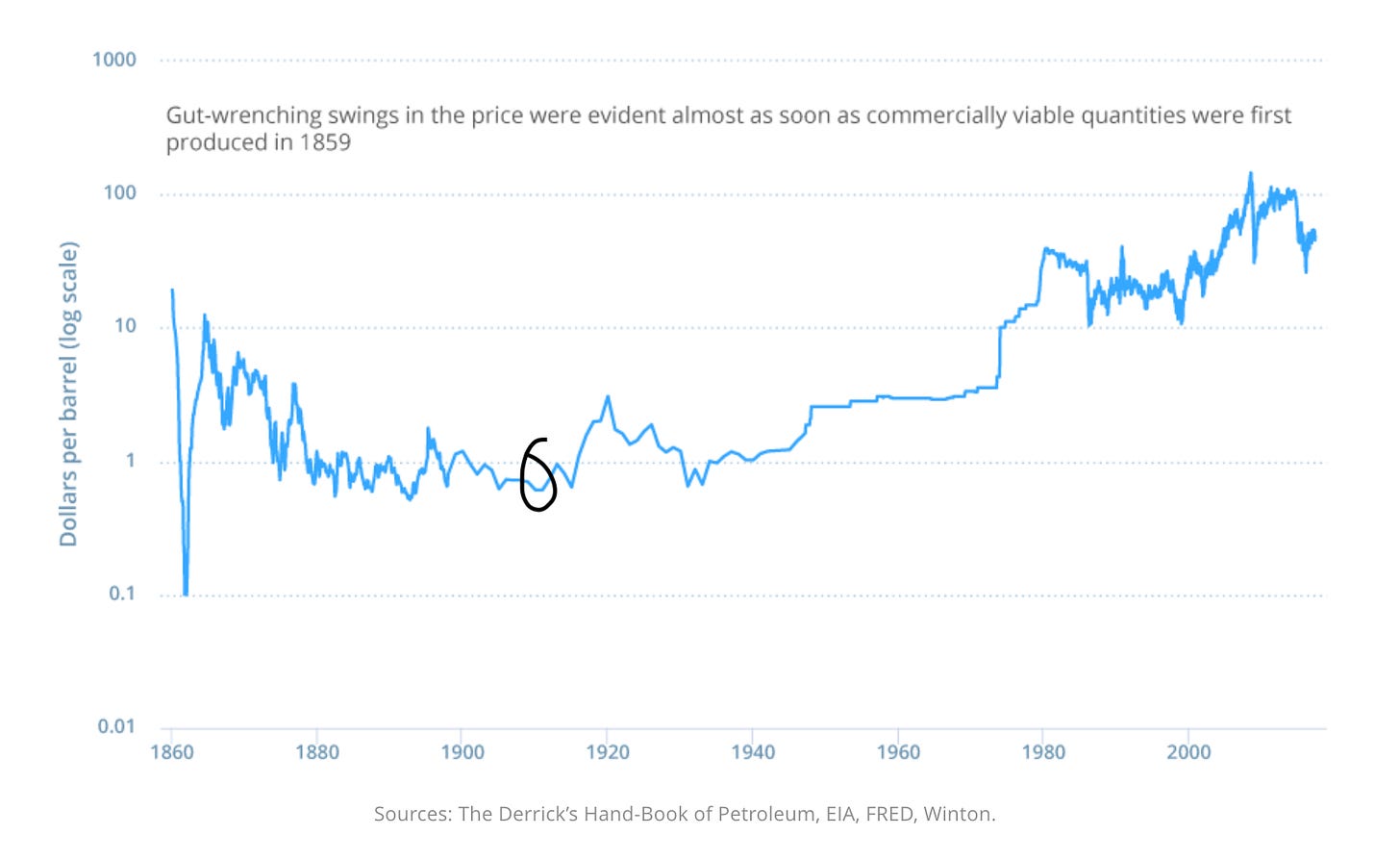

Much of the ag industry is structured around one thing: risk management. Ownership structures, commercial agreements, procurement models….all largely built around the equation of risk relative to reward.

Risk seekers want room to roll the dice to maximize upside, risk mitigators want to minimize the downside.

Almost every decision about buying or selling a commodity (however loosely defined) can be distilled down to an implicit risk/reward equation.

The setup:

A common model in US cattle feeding is retained ownership, in which a cow-calf producer or stocker will retain ownership of their cattle through the feedyard instead of outright selling the animals to the feedyard. If they sell the cattle to the feedyard then the feedyard owns the production & market risk on those animals, whereas if they retain ownership of those cattle then the producer or stocker owns the production & market risk on those animals.

Retained ownership of calves through feeding is not an uncommon model and it can have interesting implications for behavior. For example, a cow-calf producer who is going to make or lose money based on the live performance of an animal in the feedyard might make different decisions early on than a producer who sells weaned calves at the local auction barn.

Meanwhile the transaction between food retailer and packer remains largely the same: the retailer forecasts how much of each SKU they will need for any given time period and what price they will pay the packer. Of course there are different flavors on the transaction but at the end of the day it all comes down to $x per pound * y pounds = total amount retailer owes packer.

This standard arrangement has implications:

(1) The burden of forecasting how much fresh meat will sell through the meat case rests with the retailers.

But demand planning is a tricky business. Underestimate demand and the meat case will sit empty, overestimate demand on fresh meat that has a very real expiration date means when that meat is sold in the spot market it’s a fire sale situation.

Both are bad. So this capability of demand planning is critical to the P&L of the meat department at any retailer. Part of the challenge is that you’re forecasting multiple variables at once; get any one of them wrong and you get the whole picture wrong.

(2) Then there’s the portfolio effect for retailers.

Aka how the meat case lever is positioned within the food retailer’s broader strategy.

(3) Meanwhile the big challenge for packers is the idea of balancing the carcass.

Balancing the carcass means selling the primals at an equivalent rate relative to their percent of the carcass. This is a continual high-wire act because not all cuts are in equivalent demand at any one time, it’s why in times of high wing demand chicken processors wish for an 8 winged chicken.

The thought exercise:

So let’s apply that retained ownership model to the meat case and play it out. What if the retained ownership model was used by packers to retain ownership of fresh meat through the meat case until the end consumer purchases it?

This would mean retailers could adopt what cattle feeders call the “hotel model” where the cattle feeder gets paid a flat rate by customers for the use of that space (and management, feed, meds, etc). So imagine the retailer gets paid a lease fee by the packer for the use of their retail meat case.

In theory, it completely shifts the burden of demand planning to the packer who….drum roll please….has an even bigger incentive to get demand planning right.

One meat industry friend put it this way when I posed our scenario:

“

It would allow packers to be radical in retail pricing to balance the carcass.An example is strips and ribeye steaks are most often priced the same at retail but the primal values are wildly different. This makes demand uneven so if we could drive pricing off actual primal values, then we could better balance demand for the carcass.”

At the highest level, I’d summarize the pros & cons this way:

Although, perhaps you could make the argument that for those retailers who are less good at demand planning and therefore often have revenue loss from being out of stock or fire sale’ing excess fresh meat, perhaps on a net basis they could wind up in a better position through this model?

On the other hand, for some packers the idea of a bird in the hand (relatively fixed price per pound) might be better than the potential upside of the riskier model.

But let’s say this became a thing. If packers can own the meat through the meat case at retail, why can't the stocker who retains ownership of their cattle through the feedyard, retain ownership through the plant or all the way through the meat case?

The absurd thought experiment:

Now let your imagination really run wild, what if a cow-calf producer could retain ownership all the way through the meat case?

This would take deep pockets because the cash cycle in this scenario is 18+ months. That’s a while and likely few producers would have the appetite for that type of timeline unless the return were significantly higher.

It also makes me wonder if this type of arrangement wouldn’t lead to more vertical integration into cow-calf production. Specifically, it makes me wonder what would have to be true for vertical integration in beef to happen at scale, but more on that another time.

But maybe this is all silliness and would never happen for reasons I’ve totally missed here:

- I’d love to know those reasons.

- What’s a better hypothetical alternative to business as usual at the meat case?