Today’s newsletter is less learning out loud & more processing out loud.

Annie Duke is a former professional poker player. She’s written a couple of great books on decision-making frameworks but her latest book, Quit: the power of knowing when to walk away, is next level.

Before we get to why Quit spoke to my soul, here are my favorite ideas from the book:

“Grit keeps you working on worthwhile things, but it also keeps you working on things that are not worthwhile.”

The central idea is that our culture celebrates grit even tho sometimes quitting is the better decision. The superpower is in knowing when something is no longer worthwhile, no longer worth gritting it out…knowing when it’s time to quit.

This isn't quitting when the going gets tough, as it always will in anything worth doing. This is building the really hard-to-build muscle of knowing when to grit and when to quit, how to avoid quitting too early OR too late.

“The skill of optimal quitting is what separates amateur and pro poker players. The desire for certainty, to know the outcome, is what keeps us playing to the end. Having the option to quit helps you explore more and learn more to find the thing you want to grit out.

Quitting on time feels like quitting too early but when you quit you live to fight another day. If you feel like it’s a close call between persevering and quitting, quitting is likely the right choice. Quit while you still have a choice.”

“A common misconception is that quitting will slow or stop our progress but the reverse is true. By not quitting you miss the opportunity to get closer to your goals. When you stick with something when there are other opportunities out there, that slows you down. Quitting gets you where you want to go faster.”

“We don’t like to close accounts/games in the loss. But remember that poker is one long game, and life is one long game.”

The more time, energy, and money we put into something, the more invested we get emotionally. This is the trap of sunk costs.

If I spend another 6 months trying to make something work, I am more likely to spend a subsequent 6 months because I’ve escalated my commitment by spending 6 more months on something.

This is why the sunk cost fallacy causes us to often make sub-optimal decisions about grit or quit. I stay in this market, with this team, with this company, etc etc etc because I’ve already invested so much effort here.

Another way we escalate our commitment is by making something part of our identity.

“When we make something part of our identity it’s even harder to quit. Cognitive and motivational factors make it hard to change your mind or quit a venture, because it is part of your identity. Would shutting down this business make it a mistake to have started?”

Duke offers examples around politics (if I put yard signs up for a politician then learn new negative information about that politician, it’s harder to take the yard sign down because I’ve made my support of that candidate part of my identity to the neighborhood) and business (a founder who built his company in public while frequently railing against venture capital and extolling the virtues of bootstrapping, so when he had the opportunity and need to take venture capital to win his category, he missed it b/c he was so entrenched in the identity of being a bootstrapped founder. Even tho his company got out-competed as a result.)

💪🏽 1 – The ability to discern whether grit or quit is the best path.

💪🏽 2 – The ability to act when quit is the best path…the ability to walk away.

Sometimes quitting makes sense because something about the world changed, or the context around the thing. Sometimes it’s because we changed, maybe our context changed or life season changed, or we refined our long-term goals.

Startups, by definition, enter unknown territory. There are so many things you can’t know when you start, that you only learn once you’re in it. Sometimes you realize there’s more potential value to be created for an even larger market, sometimes the opposite. Sometimes you realize it will take longer than anticipated, or that you’re too early for the market. Startups are an ongoing flow of new information informing a series of ongoing grit-or-quit decisions.

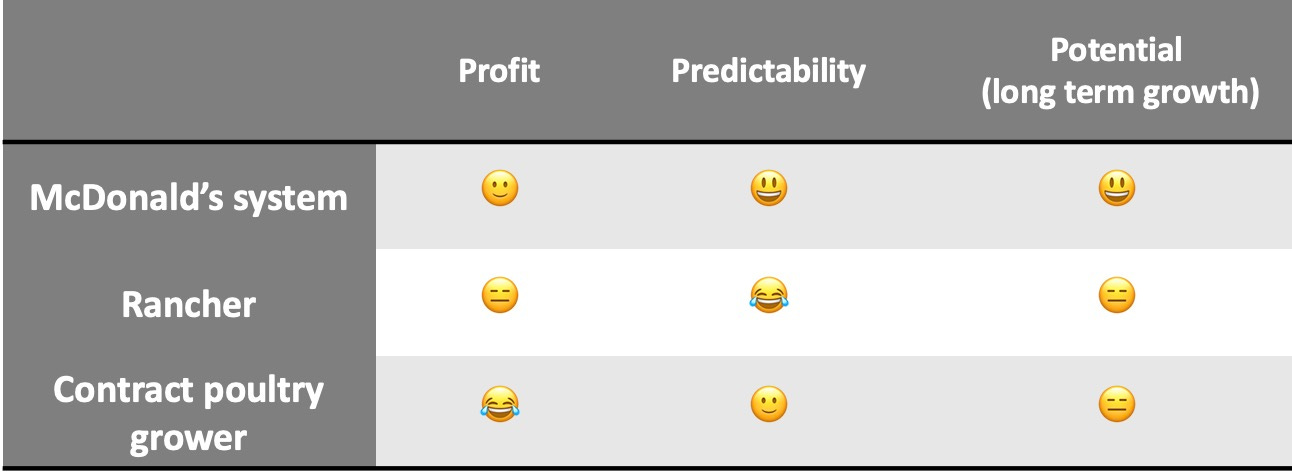

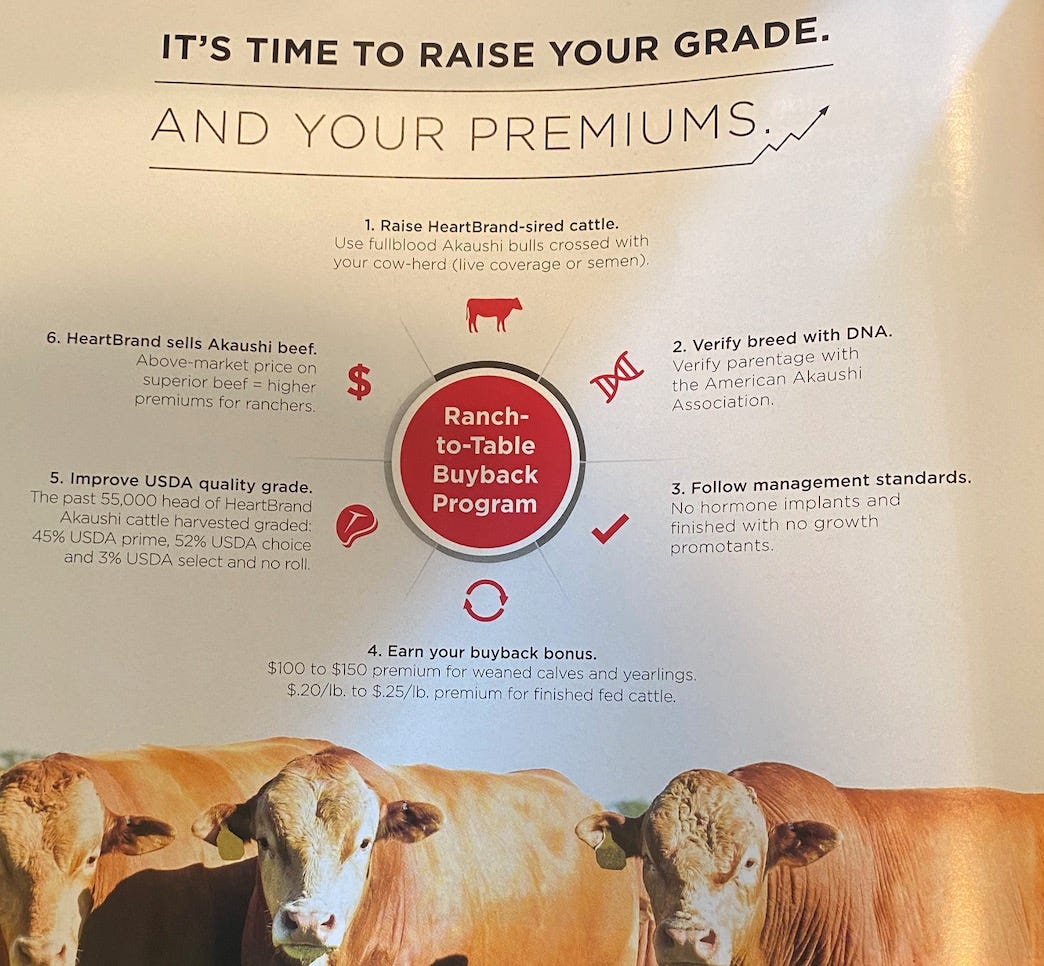

So is production agriculture, where grit-or-quit decisions range from deciding whether to quit the status quo to pursue a new market, a new customer, a new business model, new genetics, new facilities styles, etc etc etc.

For producers, maybe the better way to say grit-or-quit decisions is to call them status quo-or-no decisions. Going back to the idea that it’s easier to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally (aka quit the status quo in some way), this makes lunatic farmers all the more extraordinary.

Ok so 3 reflections as I process this book…

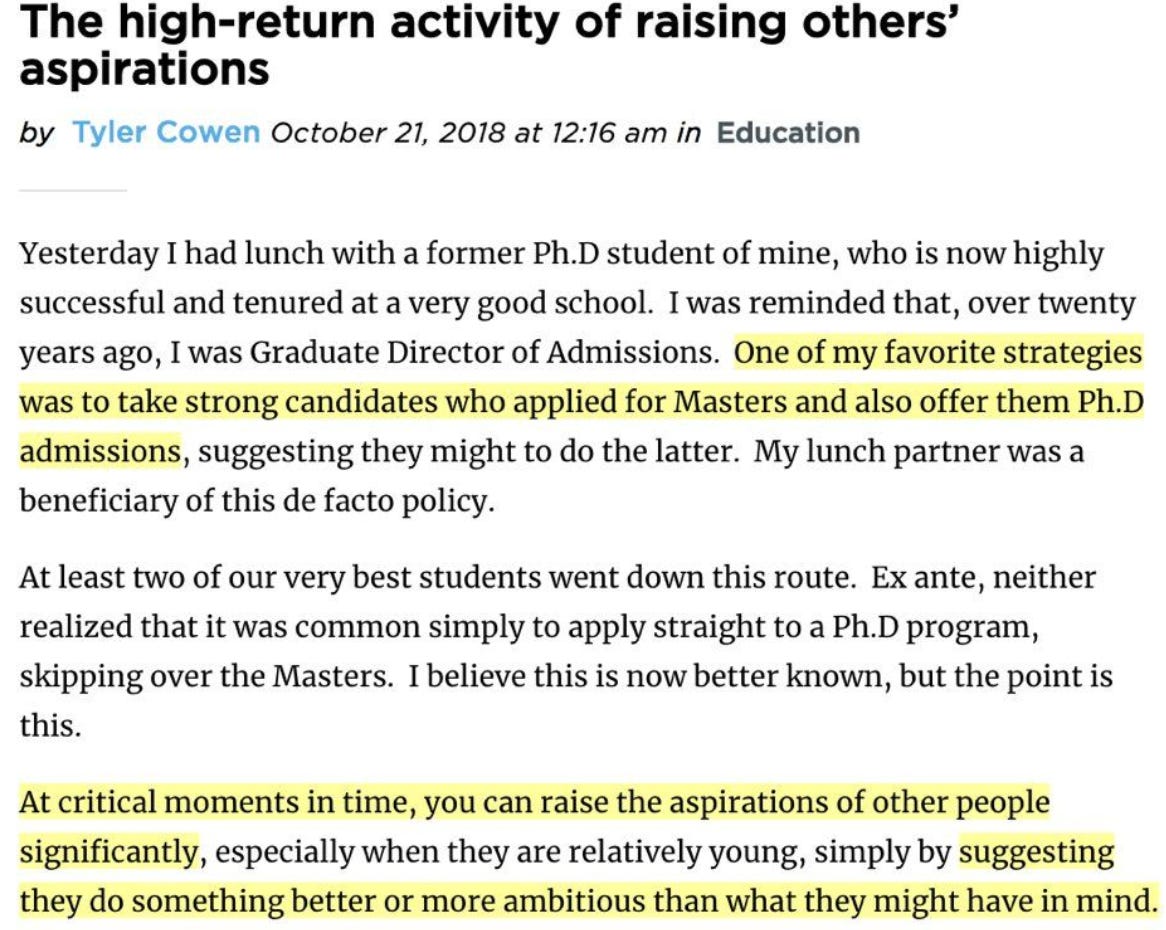

Duke refers to an idea from Alphabet’s X, the moonshot factory to “train the monkey first”. Translation: if your goal is to train a monkey to jump over fire on a pedestal, you already know how to build a pedestal, so don’t build the pedestal until you find out if you can train the monkey, which is the hard part.

So “train the monkey” is shorthand for do the hard thing first, so you know whether to continue on to the easy part, or to quit and move to the next hard thing.

It’s easy to confuse activity with progress, but being busy with easy things just punts the decision to grit-or-quit….which we know makes the decision even harder because of our escalation of commitment & the sunk cost fallacy!

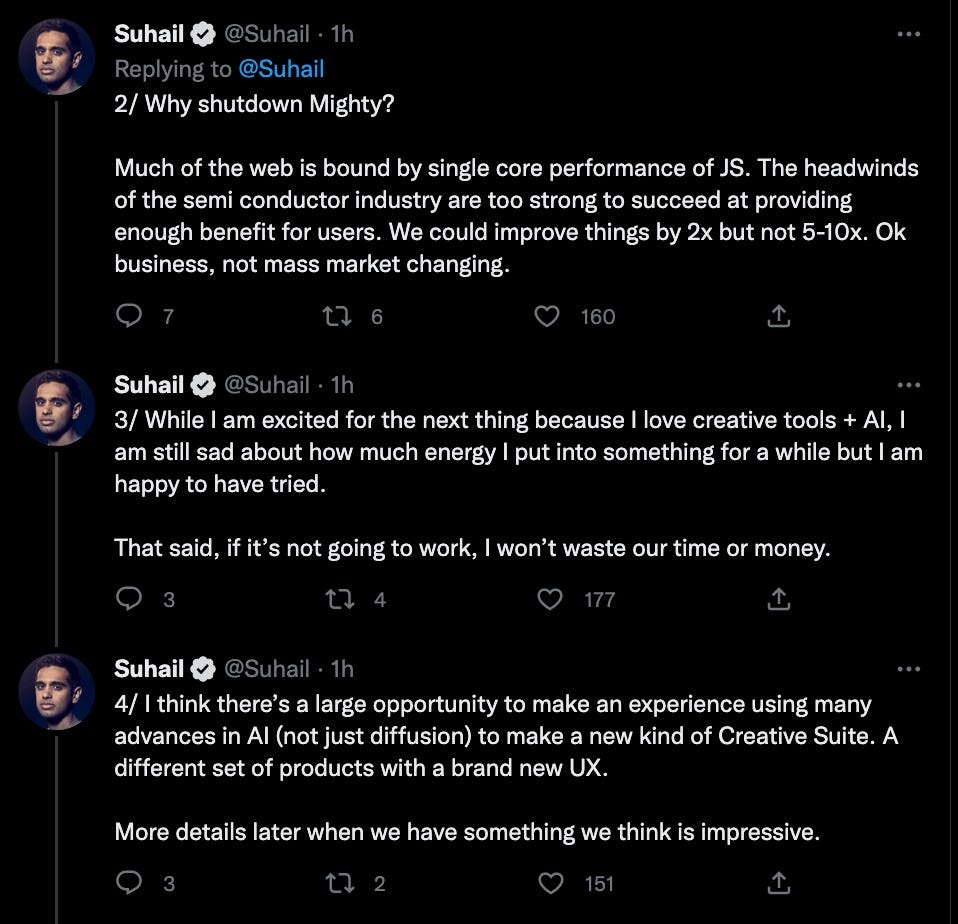

As I was writing, I stumbled on a founder announcing that he’s shutting down his current company because they realized they couldn’t do in the market what would make it worthwhile to grit:

This is a founder whose first company (that he left to start this company) is seemingly successful, so he likely has a good feel of the difference between “if we dig in we can breakthrough this problem” and “this problem isn’t worth overcoming”.

There are grit or quit decisions that are small, like whether to keep working a sales channel or keep using a specific genetic line. And then there are big grit or quit decisions, like jumping industries or rethinking our business model.

My hardest quit decision ever was to shut down my first venture. Somehow, by some miracle, this nobody from nowhere kid had found a massive problem that needed solving. We had some customers, a few investors, a product and a team. I was doing The Thing.

I spent ~30 months working on it, and if I had been more discerning at that time about whether to grit or quit, I would have spent <6 months on it. I say that with not one ounce of regret, and of course with the benefit of hindsight.

But the signs were there, I just didn’t want to see them. I wanted to do The Thing and if we could just work harder or be smarter, we could figure it out….right?!?! Wrong.

When I decided to quit, ~40% of investors’ money was still in the bank. We didn’t run out of cash; I spent too much of myself trying to make this one thing work that by the time I realized I would need to take a completely different approach, I didn’t have it in me to shift gears. I ran out of mental and emotional energy, I had nothing more to give to this problem/customer/company.

So I returned the remaining capital to investors and shut the virtual doors.

I knew in my bones it was the right thing to do, but OOPH it felt like I was making a naive/foolish/bad decision. I had never heard of someone returning capital like that because the only startup stories you hear are about either an exit or running out of cash. The message I interpreted from the startup ecosystem was ‘real founders don’t return capital, they keep going and figure it out…they grit it out.’

There have only been two times I’ve had external validation of my decision. The first was a few years after the fact when one of the investors said he had multiple active early-stage investments where the startups had no chance of survival but the founders were clearly going to spend every last dollar, and he appreciated that I returned the capital once the writing on the wall became too prominent to ignore. (He also said he’d invest in my next venture so I hope he’s reading this and still thinks that😉)

The second was reading Annie Duke’s book where she says:

“There is no honor in spending investor capital when you know the company is failing. Returning capital increases odds investors will back you again. Founders also feel like they owe it to employees to keep going but life’s too short to keep going when something is failing, for investors and employees.

Once it’s clear the venture isn’t going to be successful, everyone should get out – founders, investors, employees.

Don’t spend good time after bad, or good money after bad."

Shutting down a company is a particularly heavy decision because there are investors and employees and customers involved. And ego, so much ego. So much self-identity. So much escalation of commitment.

But again, this whole idea is NOT simply quitting when the going gets tough, as it always does in anything worth doing. It’s about building the really hard-to-build muscle of knowing when to grit and when to quit (and to what degree), arguably one of the hardest things for an innovator to distinguish.

Maybe I only liked this book so much because it provided confirmation bias…but I think it’s more than that. Knowing when to quit, and when to grit, is this wildly important skill that NO ONE TALKS ABOUT even though every day we implicitly make hundreds of grit-or-quit decisions.

So that’s my new #goal, to wisely wield those two little words like a scalpel, carving out a path of effectiveness and impact over the long run:

I quit.