First we looked at how the ‘beef on dairy’ genetics strategy will impact cow-calf producers. Spoiler alert: not much, mathematically speaking.

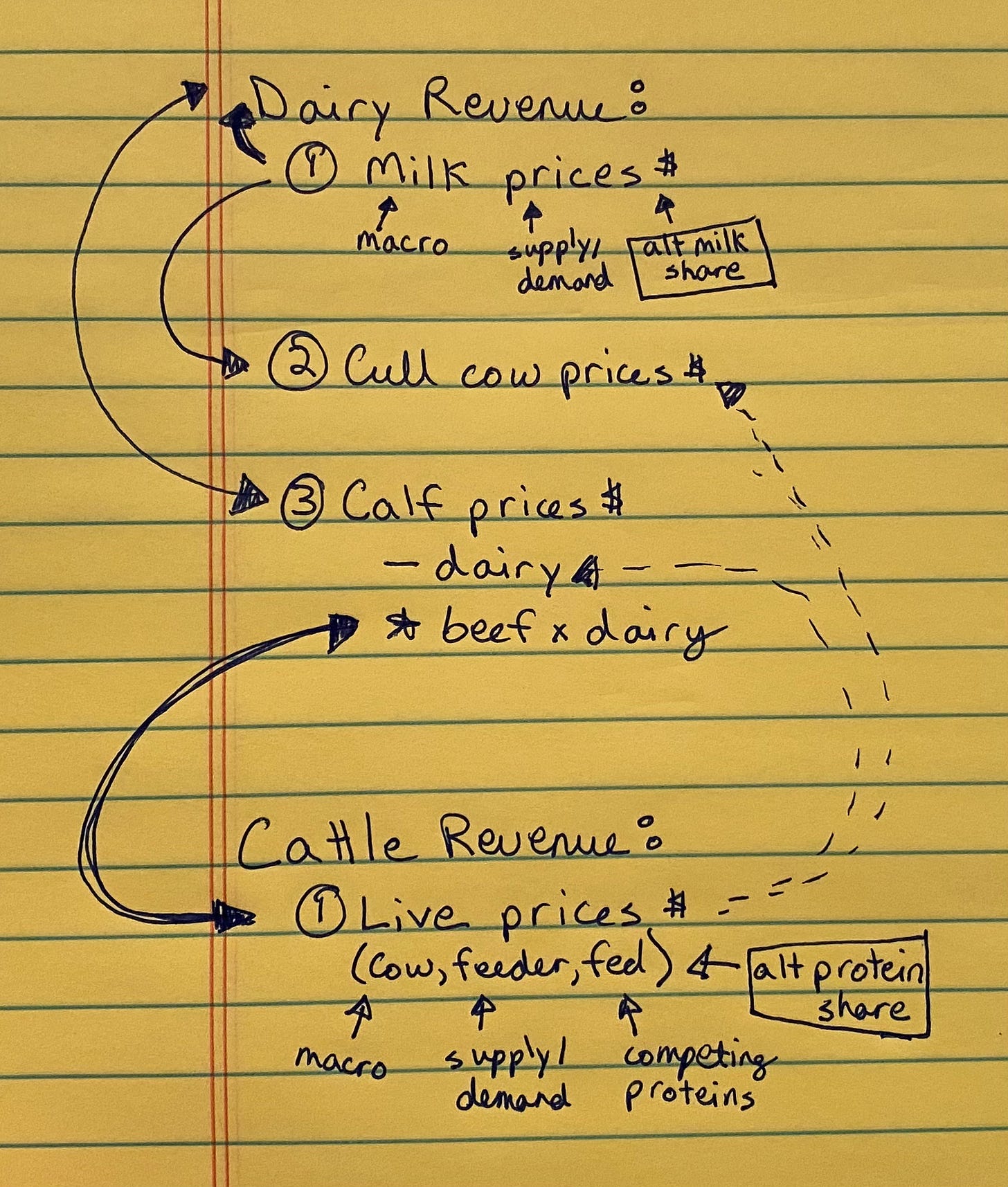

Then we looked at what’s driving this beef on dairy thing from the dairy producers POV. tldr: its complicated.

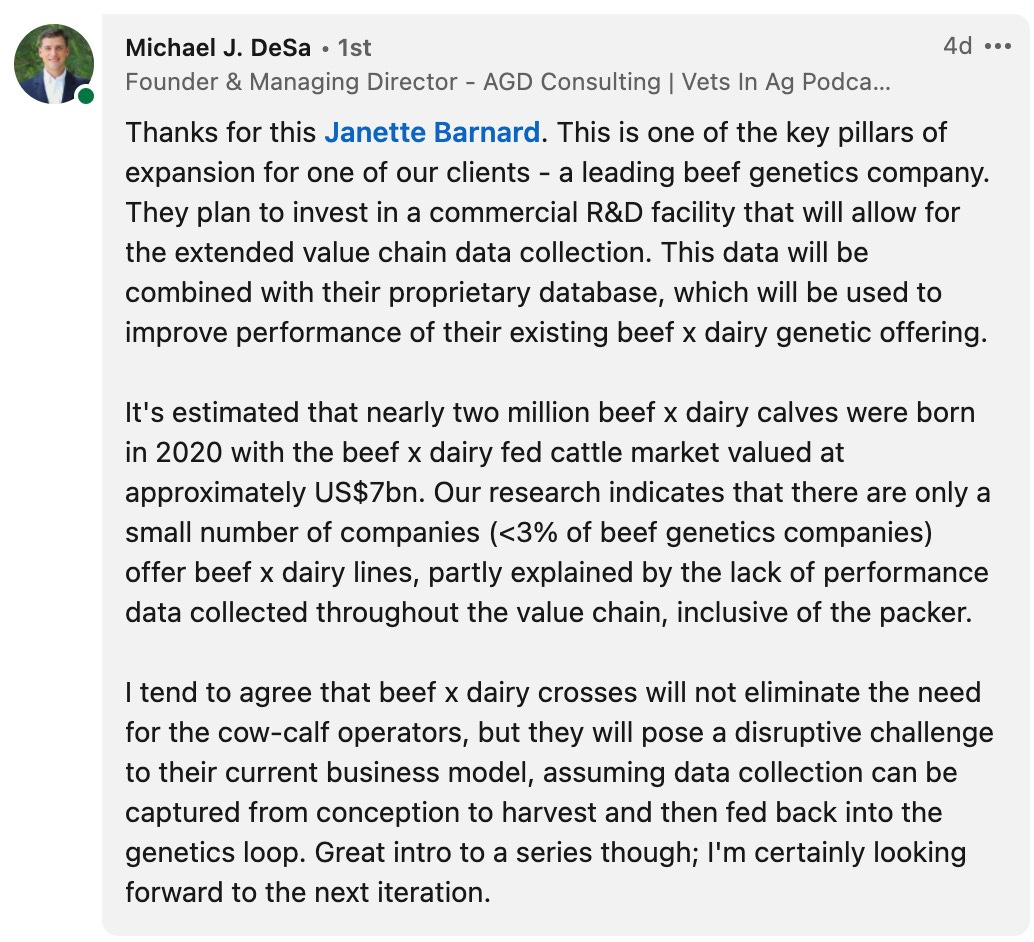

I’ve been exploring the implications for cattle feeders, packers, and retailers and next week we’ll talk about those. But first I have to share 3 big aha’s that have jumped out as potential beef industry game changers…here we go.

(1) Beef is better, right? …right??

I started this series with an assumption that beef breeds create better beef carcasses than dairy breeds, or dairy x beef crossbreds. (It seems reasonable, doesn’t it?)

But here’s the surprising little secret: Beef x Dairy cross carcasses are as good or better than straight beef carcasses, or ‘natives’ as the people say.

Texas Tech recently published trials looking at how beef-dairy crosses perform in feedyards and in the plant, and my takeaway was that beef-dairy can increase total pounds without sacrificing quality grades, when managed correctly. That’s a big deal. Imagine being able to sell 100 additional pounds of meat per animal with minimal yield impact.

Someone framed it this way: milk production and red meat yield are antagonistic traits and tend to move in opposition directions, while marbling and milk production are complementary traits and tend to go hand in hand. The beef on dairy genetics jigsaw puzzle allows dairy producers to make decisions that get the best of beef and dairy breeds, to use ‘elite terminally focused genetics’ on the beef side that offset the dairy deficiencies. For example, one variation on a beef on dairy program might be to use Limousine sire genetics (high red meat yield) on Jersey females (high marbling). All breed genetics are not the same, that’s just one example of how the jigsaw puzzle can be put together.

It’s how dairy producers thread the needle to keep the best of dairy genetics so milk production isn’t negatively impacted one ounce (which would be a complete deal breaker for dairies, obvs), while driving towards carcasses that have zero hint of dairy’ness to them and are therefore just as valuable as carcasses from beef genetics.

(2) Consistency is the name of the beef on dairy game

There are 3 elements of consistency that beef on dairy can offer to the beef value chain:

- Year round continuous supply of calves to the feedyard, and then to the plant.

- Genetic consistency given how narrow the genetic base of dairy cattle are since AI has been used so widely for so long.

- Management consistency – while a beef animal could move through 2-3 sale barns between weaning and arriving at the feedyard, beef-dairy crosses are much less likely to go through a sale barn at all. They’re more likely to move in large lots from calf ranch to grow yard to feedyard, or directly from calf ranch to feedyard with consistent management in each phase.

The US beef industry has been wildly successful at increasing consistency of meat so that the consumer experience is what the consumer expects, every time. And yet, there is still a lot of variability in genetics and production systems and feeding and management and, and, and. With 800k+ cow-calf producers and animals changing hands multiple times, high variability is somewhat of a given.

But beef dairy crosses offer the exact opposite of fragmented traditional beef production. This segment offers a hyper consistency of product which can only be net positive for processors, retailers, and consumer eating experience…which is net positive for all players upstream.

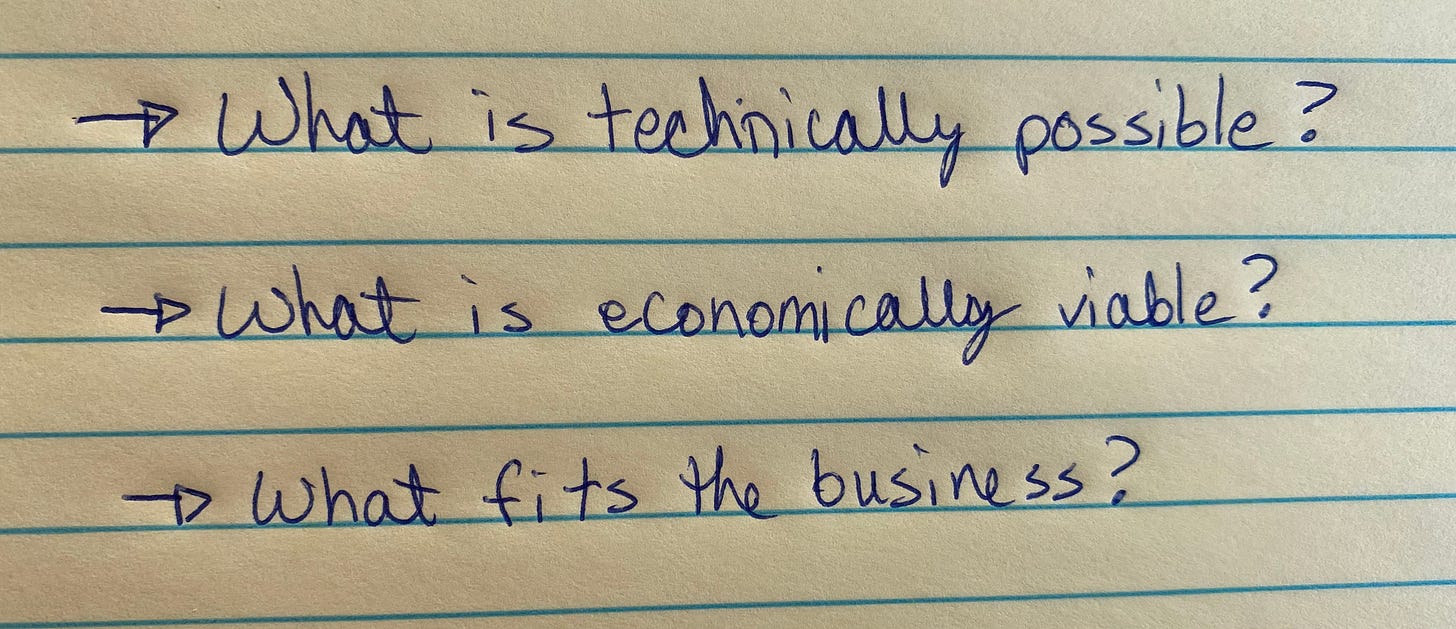

(3) Max value capture requires aligned supply chains

Value is only value when it’s recognized by the buyer, in this case the packer. The value chasm is wide between a dairy animal and a beef animal, so the challenge for beef-dairy animals is to get them priced like a native. One producer said it this way, “packers are looking for a reason to price a beef-dairy cross like a dairy animal. You have to get the animals on a grid to get a base price where it should be.”

The beef-dairy value equation is driven by the price the packer is willing to pay; the value of the animal to the packer determines the value of the animal when it first hits the ground. If the packer doesn’t recognize the value of a beef-dairy carcass, then the beef on dairy strategy doesn’t pencil out for the dairy producer.

Capturing full value of the beef-dairy animal requires closely aligned partnerships all the way through the value chain to the packer. Aka aligned supply chains or coordinated supply chains. Prime Future readers who have been around for a while know I have a borderline obsession with how aligned supply chains can create better outcomes for producers and consumers. We’ve talked about them here and here, with this key idea:

“Traceability is meaningless until somebody will pay for it. The industry has thrown around the t word for at least a decade with extremely limited success in finding the right use case & corresponding business case. Like all innovations, until the right business case surfaces it’ll never happen. However, coordinated supply chains likely are the business case that supports traceability particularly when the data flows in both directions so producers get better feedback on how animals perform in the feedyard/plant, and consumers get relevant cues about how the animal was produced.”

But beef on dairy looks like it just miiight be the breakthrough use case to drive supply chain alignment and as a byproduct, traceability.

For dairy producers to maximize the value of beef-dairy crosses, dairy producers have to create supply chain partnerships for the long term where everyone involved is incentivized to ‘stick with it’ in order to create a consistent system, and to mature the whole system over time. (one of my other favorite ideas is playing long term games with long term people – traditional transactional won’t work here!)

Will it be surprising if Dairy Beef aligned supply chains grow and consolidate over time to find the efficiencies of scale without the capital intensity of true vertical integration? Not at all, that’s the nature of the agriculture game.

So there they are, the 3 ideas that make beef-on-dairy shine:

- Beef x Dairy cross carcasses are as good or better than straight beef carcasses. (Think of it as having your cake and eating it too, but ya know, beef.)

- Beef-dairy crosses hold a consistency advantage over the traditional fragmented beef value chain.

- Beef-dairy cross value chains are forcing new partnerships in order to capture full value at the packer level.

Which is all fine and well, until we come back to the math of beef on dairy. If we are really only talking about 5M calves annually, out of 25 million total fed cattle, it raises the question of….so what?

What happens with 5M beef dairy crosses is interesting, but the really fun part will be seeing how the 5M could influence the 20M.

It’s almost like The Innovators Dilemma, but at an industry level. Here’s my short summary of The Innovator’s Dilemma:

“When big companies are disrupted by upstarts, many assume it was because the big co didn’t see what the upstart saw, e.g. Kodak, Blockbuster. But author Dr. Clayton Christenson argues that big companies see the early trends just fine, they just are not positioned, structured, or incentivized to act on early trends. Leaders at established companies have to focus on market share and profitability of today’s largest customers. This is rational behavior. But it also makes it easy for incumbents to miss emerging trends.”

Here’s a recent take on that idea:

“The reason big new things sneak by incumbents is that the next big thing always starts out being dismissed as a “toy.” This is one of the main insights of Clay Christensen’s “disruptive technology” theory. This theory starts with the observation that technologies tend to get better at a faster rate than users’ needs increase. From this simple insight follows all kinds of interesting conclusions about how markets and products change over time. Disruptive technologies are dismissed as toys because when they are first launched they “undershoot” user needs. The first telephone could only carry voices a mile or two. The leading telco of the time, Western Union, passed on acquiring the phone because they didn’t see how it could possibly be useful to businesses and railroads – their primary customers.”

Now read that paragraph again but where it says ‘toy’ insert ‘just beef-dairy crosses which is a tiny fraction of the beef supply, no worries’.

Imagine that cattle feeders and packers and retailers get used to all those benefits mentioned above that are inherent to the beef x dairy value chain. Now use an exceptionally limited amount of imagination to picture those expectations bleeding over into the other 80% of beef, the natives. Not much imagination required, huh?

The unknown is how the beef value chain will respond and how long it will take to catch up & recreate the rapidly accelerating advantages of the beef on dairy value chain. Is this a 30 year dynamic or a 5 year dynamic? TBD.

Perhaps beef on dairy is to beef what ABF chicken was to the US chicken industry 5-7 years ago when it was still a tiny percentage, before the tiny percentage influenced the majority. Without a doubt, there are new emerging trends in pork and poultry…maybe not as clearly emerging as beef on dairy yet, but emerging nonetheless. What are those emerging trends you see?

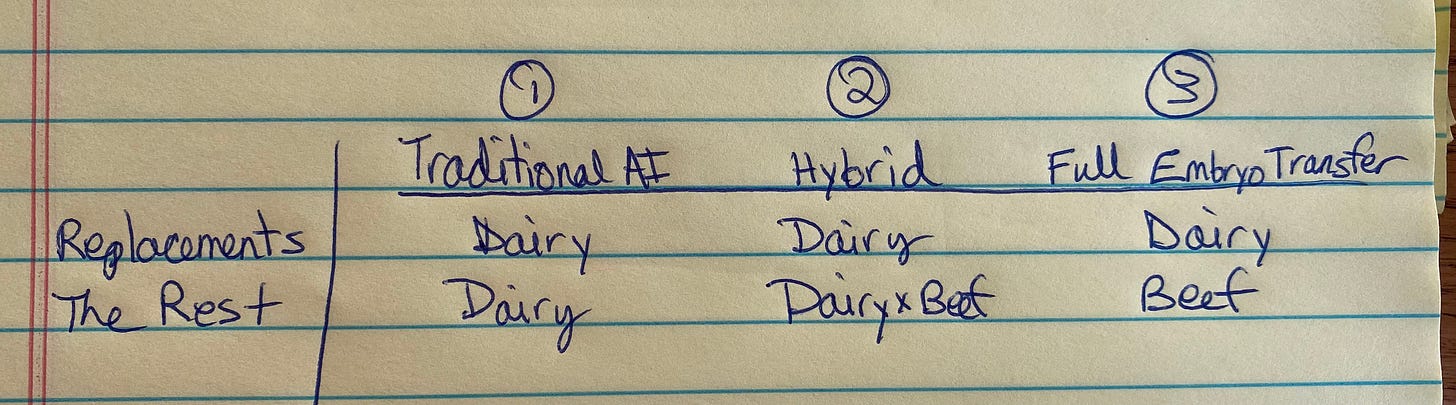

Total Addressable Market (TAM) for Beef on Dairy (updated)

- The US dairy industry has been steady state for a while at 9.4M dairy cows.

- If the herd turnover rate is closer to 40%, then we need 3.76 million replacement heifers annually.

- But…..there’s another number here, ‘return to replacement’ which is what % of heifers born intended to be replacements actually go back into the herd. If that number is closer to 80%, then the industry really needs 4.7 million heifers to be born annually.

- Assuming replacement heifers are created via sexed dairy semen and the remaining calves born annually will be bred to beef genetics for a beef dairy cross calf, that means the upward limit on cross calves is 4.7 million.

Let's call it 5 million just for a clean number.

- And though it ranges, let’s use the number 25 million cattle fed on feedyards annually.

So beef on dairy as a percent of total fed cattle looks like it will max out at 20%, at least in the US industry.

Beef on dairy TAM = ~5M beef x dairy calves out of ~25M total fed cattle

I’m interested in all things technology, innovation, and every element of the animal protein value chain. I grew up on a farm in Arizona, spent my early career with Elanco, Cargill, & McDonald’s before moving into the world of early stage Agtech startups.

I’m currently on the Merck Animal Health Ventures team. Prime Future is where I learn out loud. It represents my personal views only, which are subject to change…’strong convictions, loosely held’.

Thanks for being here,

Janette Barnard